No, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien are not cool

The manosphere doesn’t care about your ideals

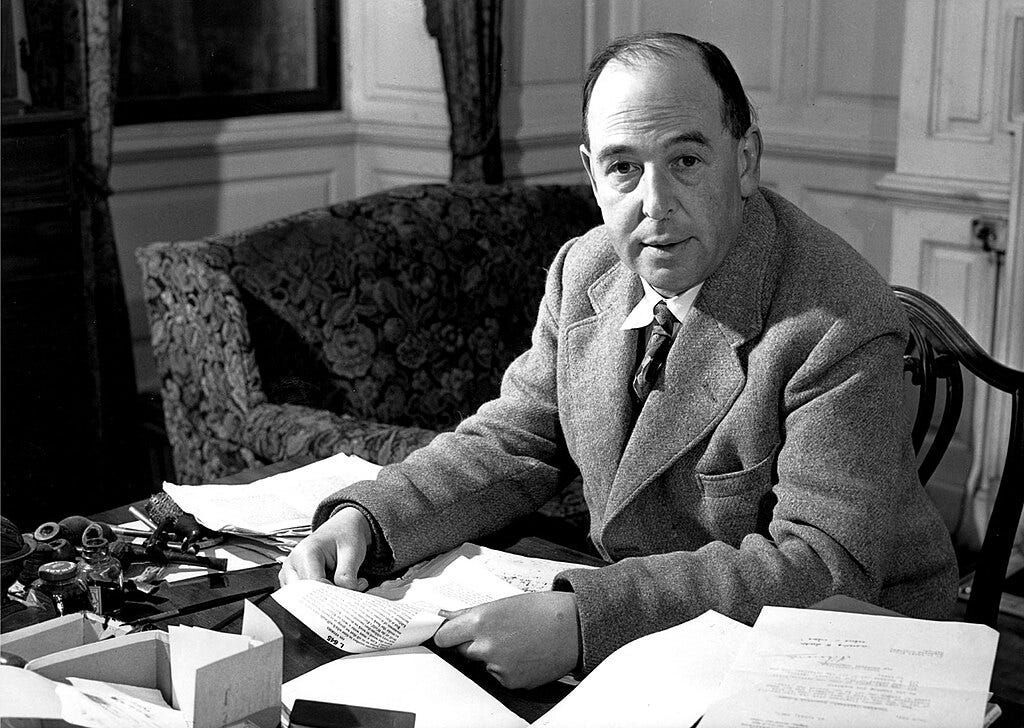

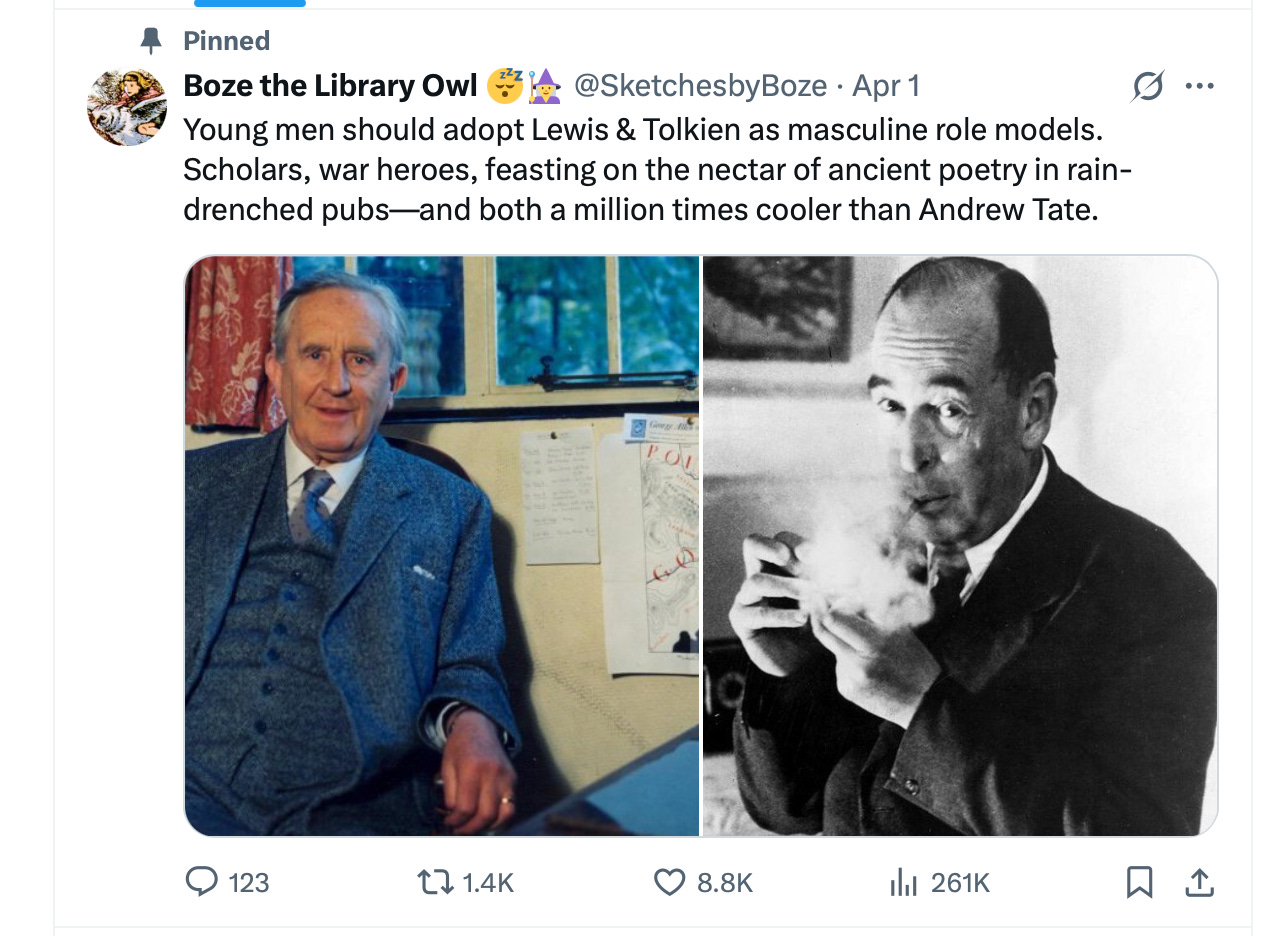

A week or so ago, a post from X user @SketchesbyBoze was making the rounds on Substack Notes, where public discourse is always whimsically delayed. In it, Boze the Library Owl opined that Lewis and Tolkien would make better role models for young men than Andrew Tate:

The post performed well on Substack, where arguably it found an ideal target audience. “1000% Add Dostoevsky,” one commenter wrote. “And they would NEVER wear shorts. Grown men wear trousers,” someone chimed in. To seal the deal: “You are so right. I’m neither young or a man and they’re both heroes of mine.”

I’m going to throw out some credentials at the outset here. I read Lord of the Rings in my early teens and it quickly became my entire personality. I read J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth and Lord of the Elves and Eldils. I watched the extended edition of The Return of the King including all 12 minutes of fan club credits. I know that Viggo Mortensen broke his toe when he kicked the helmet, and I used to own his audiobook of The Little Prince on CD. I downloaded an app to teach myself Elvish. I started reading (or being read) The Chronicles of Narnia around eight years old, and I’m part of the way through probably my 15th or 16th reread of The Silver Chair right now. I once dreamed I met all four of the Pevensie actors after the first movie came out. In about seventh grade, I had such a big fight with my best friend about whether C.S. Lewis or Tolkien was better that we almost broke up. In the background of my entire Ph.D. project in theology, the imagination, and the arts was the imaginative formation that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien gave me, and I can’t imagine my life without their work.

All this being said, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien are not cool.

I am not cool either, obviously, if you couldn’t tell from the foregoing. I don’t think being cool is all that important, and I never have. But I know what it is. When I threw out my first half-baked version of this take on Substack Notes,

suggested that we might just be operating from different definitions of “cool.” This may be true, so here’s mine.We’ll start with what “cool” is not. “Cool” is not just a word for things that you like or enjoy or find fascinating or appreciate. “Cool” is not what my friends had in mind when, reading the previous paragraph, they felt the need to gush in sympathetically, “No, you are cool!” They mean that they like me, that they find me interesting, that they think I have decent style and interesting ideas. All of these things are great, and I actually value them more than being cool. But they are not cool.

As for what cool is, positively, we’ll refer (as any cool person would do) to the Oxford English Dictionary definition (8a). “Attractively shrewd or clever; sophisticated, stylish, classy; fashionable, up to date; sexually attractive.” I’m going to add here that coolness, as a personality trait, seems to require a certain amount of self-confidence, self-possession, disinterest in what others think. There’s an effortlessness to it, and perceived effort can dissolve coolness faster than almost anything else. Lorde is cool. Taylor Swift is not. Bob Dylan is cool. Justin Bieber is not. If you try too hard, you aren’t cool.

But more than anything else, being “cool” is a public consensus by people with taste. When I was in college, David Foster Wallace, Lana Del Rey, Pabst Blue Ribbon, and green pants were cool. This was not quite by democratic decree. A group of cool people (who generally possessed, or projected, the kind of self-confidence and disinterest described above) were the arbiters of taste. More people on the college campus as a whole may have enjoyed Maroon 5 and wearing fedoras. But that didn’t matter. They were not the arbiters of taste.

Of course, this subjective element means that, to some degree, there is a possibility of totally disconnected bubbles of “coolness.” I don’t actually think that the Sigma Chi frat brothers thought that the David Foster Wallace crowd was cool, and the feeling was mutual. They all may have shared a disregard for what other people thought, and all may have been cool in their own right, but they were not cool to one another. So there’s a relativity to it. But that doesn’t mean anyone and everyone can be cool, at any moment, for any arbitrary set of good qualities.

Which brings us to young men and Andrew Tate. I’ve been wanting to write about Tate for some time. Here’s how far I’ve gotten:

Ultimately, I decided that he wasn’t worth my time or yours. Andrew Tate is obviously a bad person. I also don’t think that he’s cool to any significant degree—any coolness points he might get for being stylish and conventionally attractive are probably canceled out by his clearly obsessive craving for attention. The people who think he is cool are probably mostly in high school or even middle school. Maybe compared to them, he is cool (probably because the bar for self-respect is on the floor).

Here’s the issue I still have with the tweet, though. We can’t pull out some middle-aged English writers from the 1950s and hold them up as models for coolness for young men today just because we like them. And it frustrates me that we would consider trying to do so, because if we want to find someone cooler than Andrew Tate, for heaven’s sake, how hard can it be?

“Coolness” is a morally neutral category, but it is also its own category: not reducible to things that you think are praiseworthy or beautiful or even powerful. C.S. Lewis said of The Lord of the Rings, “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron.” That is the best description of the book I have seen. Lewis and Tolkien wrote works which are profound, inspiring, uplifting. They can transform our whole experience of the world. “Cool” is not the word for them.

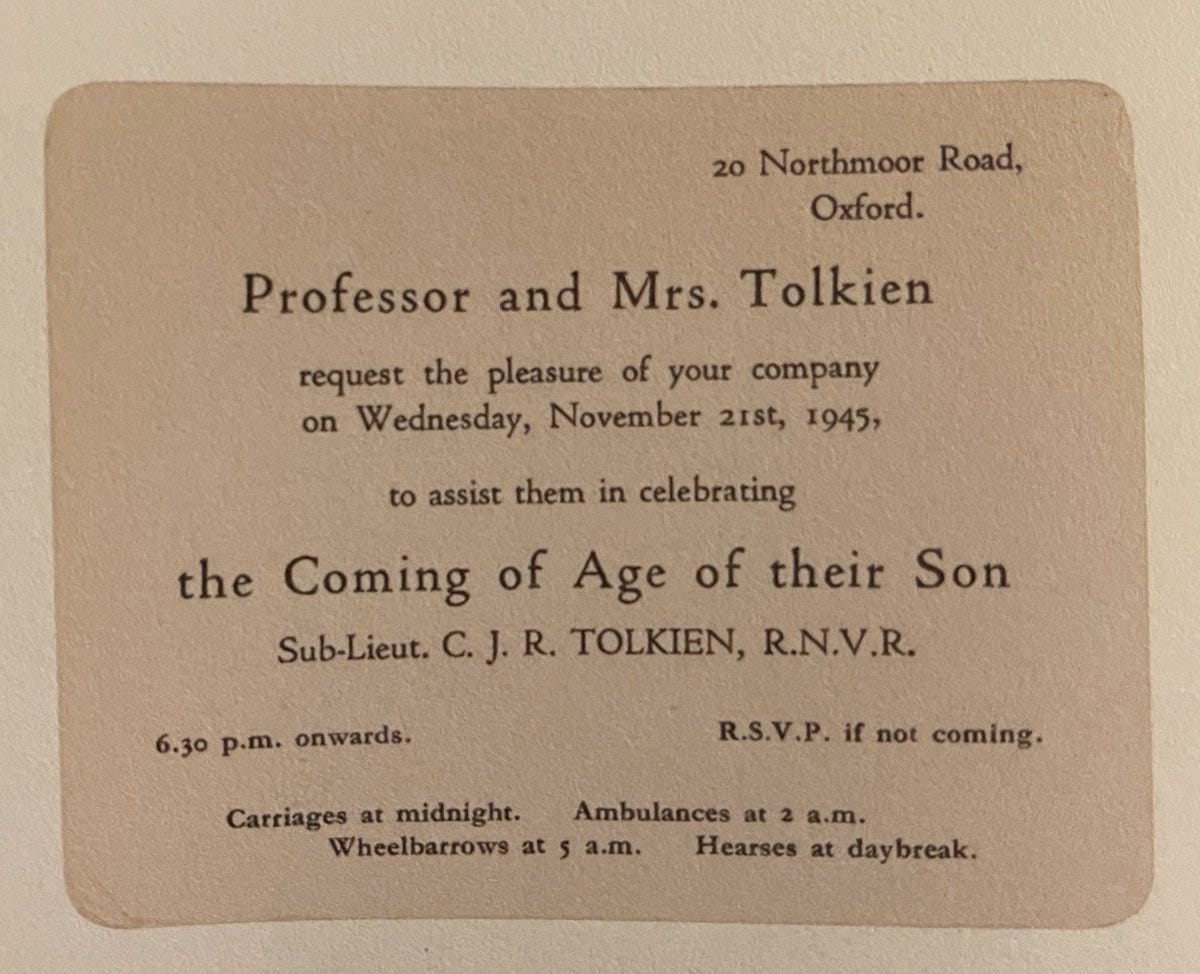

And “cool” is also not the word for their writers, who once showed up to a non-costume party dressed as polar bears. Tolkien famously gave mumbling and inaudible lectures and interviews. Both of them were professors. Yes, they both bravely served in their youth in World War I. But they rose to fame at a ripe middle age, and chose to leave as their legacy a love for the warm, humdrum things of the world, philology, philosophy, the power of beauty to communicate the meaning of life. Tolkien and Lewis aren’t famous as “war heroes”—they are famous as writers. They are famous for virtues like wisdom and wit and wonder, virtues that correspond to a healthy middle age.

If we really care about young men in the modern “manosphere” as much as we say we do, we have to do better than proposing to them virtues and models that are of no interest to them in the present moment. I think doing so requires summoning up our own capacity for respect—not respect for the manosphere, which generally doesn’t deserve it, but respect for the young men who are coming of age in a world where they are frequently told they are useless. As Lord of the Rings itself indicates, different characters are called to different virtues at different times. Not all strengths belong to everyone, and we could afford to spend more time thinking about what the virtues proper to young men are—not just virtues that counteract what we see as their besetting vices, but also the virtues that shore up their strengths.

Recently, my husband and I watched a film called Combat Obscura. Or rather, we started it. The film is a documentary gathered from combat camera footage of Marines in Sangin-Kakaji, Afghanistan between 2011 and 2012. The combat cameraman, Miles Lagoze, let the film run at times when the Marines were relaxing together—talking to kids, smoking, goofing around—as well as during battle.

The film is unfiltered. The Marines do a variety of things they aren’t supposed to, which is why the Marine Corps threatened legal action against Lagoze upon the release of the film (they never carried it out). At first glance, you might think this group of young, unbelievably fit, genial guys were flippant. They goof around, tease one another, do silly things. They speak with a lightness that, to an outsider, seems totally inappropriate to the situation where they find themselves.

But when they are dragging a comrade, screaming from his injuries, to safety, with 18-year-old Lagoze himself injured but still filming, you can see that this lightness is a choice: something that enables them to do an impossible job. “You’re going home, man,” says one of the men as they load his friend into the helicopter, still under fire. “I f***ing love you, man.” The film became increasingly violent until eventually it was too much for me and we had to turn it off.

It’s easy for us to pick out the failures of young men. They are impulsive. They are unfiltered. They are too angry, or too outspoken, or too aggressive. Traditionally, these faults have also enabled young men to do what few among us are brave enough to do: to lay down their lives for the sake of others.

I forgot one more aspect of coolness. True coolness is real. I think that’s why probably most young men do still think the military is cool—because it is one of the few arenas in our own time where real challenges are issued and met. One of the biggest mistakes we could possibly make in attempting to win over young men would be to compromise on our own integrity—to try to claim things are cool that aren’t, to try to make things “cooler” for them. Like an electric guitar at teen praise and worship night, it’s not going to work. Young men need to see real bravery, real competence, real integrity from men their own age, or close to it—men whose virtues are not unimaginably separate from their own, but rather whose strengths show them that they, too, have a place in this world.

That example of virtue is far more important than coolness, but I’m not without hope that leaders will arise who are cool, too. We need in our own time not a Tolkien, but a new, doubtless very different, Eómer:

Now he looked to the River, and hope died in his heart, and the wind that he had blessed he now called accursed. But the hosts of Mordor were enheartened, and filled with a new lust and fury they came yelling to the onset. . . .

These staves he spoke, yet he laughed as he said them. For once more lust of battle was on him; and he was still unscathed, and he was young, and he was king: the lord of a fell people. And lo! even as he laughed at despair he looked out again on the black ships, and he lifted up his sword to defy them.

I commented on the original. Basically, Tolkien and Lewis are going to appeal to a totally different sort of young man. Guys who are into Tate aren't going to be impressed by a bunch of college professors who wrote books--you want an athlete who behaves ethically or a war hero (though we don't have any).

And if you think about what made them unique, it was Tolkien and Lewis's *refusal* to be cool--to ignore current literary fashions in favor of their passion for mythology and their belief in eternal Christian verities.

This is really excellent. Johann Kurtz, whose work I like very much indeed, offered his own note-sized response to the idea of 'cool' as applied to Tolkien and Lewis (short version: like you he's not a fan).

That original crosspost has seemingly taken on a life of its own. It's become the never ending Substack note. The one thing I have posted on Substack which has had further reach than anything else, and it turns out to be something someone else wrote. One would have to have a heart of stone not to laugh.

What has become clear to me is that there is an astonishing elasticity to the range of meanings people give to the word 'cool'. And I suspect - don't know - that a great deal depends on the chronological vantage point from which a person is first exposed to the very idea.

Several years ago, at my church, they did a group reading of Carl Trueman's book, "Strange New World". We had wide participation from high school to the elderly. Now I am of the opinion that Trueman's book, and it's more lengthy companion "The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self", possess substantial explanatory power about important facets of the time we're living through. But the reaction of the participants turned out to be quite surprising. Almost everyone below the age of 30 found Trueman's thesis impenetrable, because they couldn't see that the culture had changed much at all. For them, things were much as they always had been except maybe more-so. For the elderly participants, their greater natural social isolation and less intense connection to cultural flash points made them wonder what Trueman was making such a big deal about. The group for which Trueman's insight was like a bomb going off in their heads were those people who, like Trueman, had lived through the cultural changes that got us here.

I find myself wondering how much of a person's reaction to the idea of 'cool' is generational.

As I told Johann, my own reading of Boze's use of 'cool' was as an effort to draw the attention of the kind of Tate fan who is largely motivated by the popular zeitgeist of the moment. Contextualization is a thing, after all, when you're trying to persuade.

Your essay is wonderful - quite beautiful really. There's much to say about how the West is failing its young men. Too much for a comment. But if we had wanted to contrive an educational system that would intentionally deprive young men of economic viability, competence, and skill, I'm not sure what we would have done differently.

"We castrate, and bid the geldings be fruitful." - C.S. Lewis