She was truest to them in the season of trial, as all the quietly loyal and good will always be.

-Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

As an accident-prone childhood scribbler, I always identified the most with Jo March among the March daughters. I think this is the case for most people. There might be a few girls who grew up dreaming of love and marriage who say, with Meg in the Greta Gerwig movie, “just because my dreams are different from yours doesn’t mean they’re unimportant.” But most of us, when we read literature like this, identify with the girl who is “not like other girls”—who doesn’t quite fit in, who has ambitions that defy her own (prodigious) vocabulary to explain, who is turbulent and fiery and prone to waves of emotion.

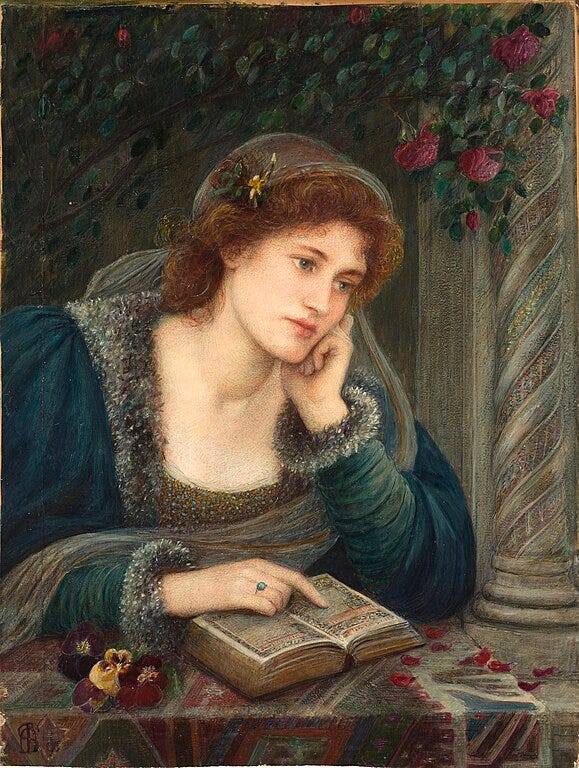

We know that not all the qualities of this heroine are good. We know that Beatrice’s wit can be too biting—that even her mild-mannered cousin Hero is willing to say so. We know that Emma can be unkind. We even know that the sainted Lizzy Bennet is too quick to judge, and has plenty of the pride and prejudice that go into Pride and Prejudice. But in the stories where they are the heroines, these flaws are given a kind of glowing light of sympathy, and characters are often put in situations where their lack of social graces—Lizzy tramping through the fields to see her sister, or Beatrice begging Benedick to kill Claudio, or Emma mistaking Mr. Elton’s attachment to her—appear more as virtues than otherwise.

This is probably because, in order to have a story, you usually need a fairly dynamic lead. Someone needs to make things happen, and frequently they make things happen by making mistakes. Since these mistakes are what give us a story, we are inclined to easily forgive them—they give us something to read about, sometimes give the heroine a chance to apologize handsomely to those she has offended by too much wit or impetuosity.

Beside the dynamic lead there is often placed a sister, or a cousin, or a friend, who is situated to set off the main character’s more brilliant light. Sometimes there are two—Meg and Beth both in their own ways showing quiet alternatives to Jo’s over-the-top personality. In even rarer cases, an author does away with the dynamic female lead entirely, and usually, this means that the book flops—at least compared to the author’s other books. Persuasion and Mansfield Park as opposed to Emma and Pride and Prejudice. Pat of Silver Bush versus Anne of Green Gables.

A criticism that’s often levied against these characters is that they “don’t have any flaws,” when in fact they do have flaws—small lazinesses and cowardices, the choice not to assert their own needs and desires, the inability to stand up to their friends over what they believe in. They have the flaws that we would least like to see in ourselves, so we refuse to see in them—flaws that are much less photogenic than an overabundance of cleverness or fortitude.

We avert our eyes from this interior drama because it would make us ask whether you can avoid big, obvious mistakes and nonetheless have significant moral failings. The character arc these characters often go through—realizing these small failings and overcoming them—does not have the satisfying catharsis of a dramatic apology or an earthshattering realization, but rather the embracing of quiet courage, more unselfrighteous humility, turning away from selfishness and toward others in small ways that will not win us any applause from fascinated masses.

In fact, by idealizing these characters we place them far away from the reality of our own everyday world, so that they cannot look down upon it with their even gaze. We call them “unrealistic.” The fact is that they are realistic, but if these characters were in our own lives, we wouldn’t notice them. Their virtues are quieter—patience and loyalty and duty. We say that they are “too perfect” when really we mean that we don’t find them interesting, that their virtues are too quiet and so are their vices.

My grandmother always says that “bored people are boring.” Proving something isn’t boring is very difficult, and I’m not sure it can be done didactically. Mansfield Park is a long book, even if you’re willing to read between the lines and consider whether Mary Crawford is a representation of Austen’s usual heroine while Fanny Price is the kind of character we usually don’t pay attention to, now given the chance to tell her own dramatic internal story. Persuasion is an easier entry point into this genre, where we can trace Anne Elliot’s initial mistake (allowing herself to have been persuaded by others out of an engagement to Captain Wentworth), her quiet courage in accepting her fate, the contrast of her character with the impetuous, shallow Louisa Musgrove, and the satisfying conclusion of the book, which I won’t spoil if you haven’t read it.

All I can do is suggest that if we spend more time with the experience of characters like these, we may realize they’re more—and less—like us than we thought. Once we’ve learned to notice characters like these, they crop up in more books than initially expected—Lucie in A Tale of Two Cities, Hero in Much Ado About Nothing, Agnes Wickfield in David Copperfield. We may even begin to recognize them in our own lives, as people we never thought had “much going on” but who quietly brighten their corners of the world. When we start to see these characters as more than window dressing, we more profoundly understand the literary works where they are at home, and we may even be inspired to grow into quiet heroines ourselves.

I'm reading Mansfield Park now so this is timely! I always want to identify with the fiery heroine but have secret fears I am no such thing. ;) So far in my reading it looks exquisitely painful to be Fanny Price!