Anne of Avonlea and the rules that make a community

Do we need to get more comfortable with being judged?

Dear readers,

Last week was a fun one—a piece I wrote titled “No, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien are not cool” went mini-viral on Substack. It was a good reminder of what an thoughtful and welcoming community Substack is; I’d expected some critical pushback for the title alone, and instead a nuanced discussion arose in the comments section, with many kind words from people I had never met before. It also almost doubled the subscriber count for Sigh No More. So if you’re here because of that piece, welcome—I’m so glad you found my writing worthwhile.

And if you missed the piece, here it is.

Warmly,

Emily

This spring, as I often do, I’m rereading the Anne of Green Gables series. The most well-known of these books is, of course, Anne of Green Gables, but there are eight books in the series, which spans from eleven-year-old Anne’s arrival at Green Gables to her sons’ service in the First World War. When I was a big-eyed and big-vocabularied seven-year-old, a teacher of mine gave me the first book, probably hoping that I’d see myself in Anne. It took a few years, but eventually I did. Now, I read them whenever I need to rewire something in my mind and heart—when I’m getting a little bit burned out, when life feels confusing or stressful, when I’m discouraged and looking at everything through lead-colored glasses.

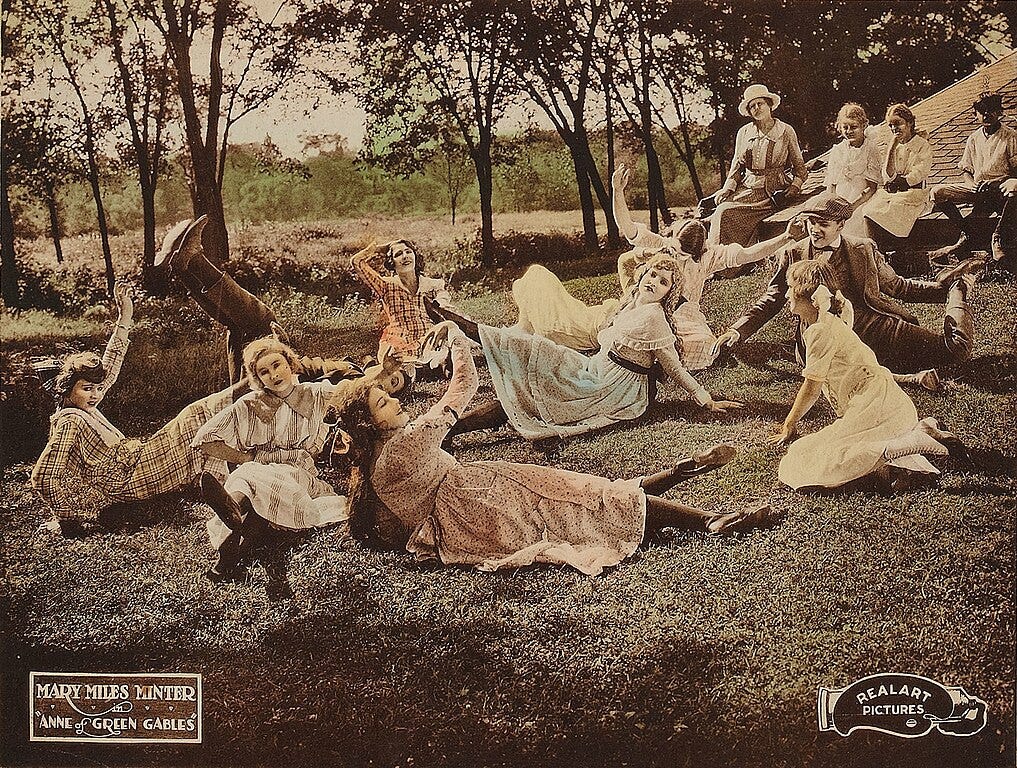

Anne never fails to uplift my perspective, with her vivid imagination, her attentiveness to all that is around her, her vivid awareness of nature and the seasons and the quirks of human beings. One of the most prominent features of the first book is young Anne’s propensity to get into “scrapes”—from putting liniment instead of vanilla into the cake for the minister to jumping into a spare room bed on top of its aged occupant.

What struck me on this reading of the book, though, is how much Anne’s “scrapes” are set off against—in fact, really only exist within—a society in which much is preplanned. The most fascinating aspect of this series for me this time around was the elaborate set of largely unspoken rules that govern life in Avonlea, mostly glimpsed through careless asides—references to when it’s appropriate for a young girl to lengthen her skirts or wear her hair up, hand-wringing over having only two kinds of preserves for the minister, the awareness every housewife in Avonlea seems to have of the quality of housekeeping of all the others.

The most vivid example of this is in Anne of Avonlea, where the Avonlea Village Improvement Society, through a dreadful mix-up, has the village hall painted blue instead of green—“a deep, brilliant blue, the shade they use for painting carts and wheelbarrows,” says a horror-stricken Jane Andrews. The A.V.I.S., as it is known, never lives down the shame. In fact, the blue Avonlea hall becomes a byword for all the surrounding villages. Why? Because of an arbitrary cultural scripting that is so foreign to us that it feels like it comes from not just another country, but perhaps another planet.

Recently, Alex Kaschuta wrote an excellent piece for Fairer Disputations on modern dating norms. In it, she writes:

Attributes left unused will inevitably atrophy. This extends to social skills and the people who need to develop them most: young men. Socialization among males, including roughhousing, teasing, and in-person verbal sparring, used to teach boys how to tolerate awkwardness, risk embarrassment, and grow from uncomfortable experiences. It helped them find their niche, whether through competence, humor, or strength. It gave them the muscles for social life. Socializing with girls also has a lot to teach young men—about sexual difference, sure, but also about our common humanity. Exposure therapy is still a very underrated teaching method. It works with spiders, and it works with your neighbor Jessica.

In Anne of Green Gables, Anne experiences this “exposure therapy” continually—being forced to go and apologize to Mrs. Lynde for her furious outburst; learning to get along with schoolmates through methods that are excessively harsh to modern eyes; being expected to attend church like other people do, do housework like other people do, make polite conversation like other people do.

There’s a trend lately among think-piece writers to point out that if we don’t have a coherent community in contemporary life, it’s our own fault. A particularly well-written (and spiky) piece on this point recently was “you’re a b***h, and that’s why we lack community,” subtitled “the ‘put yourself first’ epidemic is making us worse.”

You don’t want to feel alone, but you don’t want to be responsible for anyone else’s need. You want warmth without effort, closeness without cost. You want connection that doesn’t ask you to change your schedule, your plans, or your mood. In other words: you don’t want community. You want comfort.

The author makes some excellent points. I think she’s absolutely right about the way we prioritize ourselves over everyone else being a real problem for building anything that has any semblance of communal coherence. I feel the inclination in myself every day—why not work at a coffee shop instead of showing up to craft night? Why not stay home, fiddling with my sourdough and my Roomba, instead of going to a party with people that I don’t know? Interaction with others is a risk, and in an increasingly polarized world where screens consistently show us the absolute worst of other people, it feels riskier. Consistently, most of us fail to rise to that occasion.

But I also think that the critique of individuals for failing to build community can itself be a bit individualistic. As I’ve written before,

American culture, and the commentary upon it, takes individualism as an unnoticed given. You can stop scrolling social media. You can invite more people to dinner parties. You can maintain your friendships by giving each of your friends time slots once a week. . . . Community isn’t really meant to be an individual project, or even a group project. Shakespeare’s plays, like most contemporary sitcoms and most successful pieces of literature, take community for granted—community is the backdrop against which the story unfolds.

And community, in Anne’s case, means not just the warm and welcoming Avonlea that embraces her and provides her with a life and a home, but also the judgmental, stick-in-the-mud Avonlea that thinks she is probably clinically insane. It means an Avonlea where a million unwritten rules about dress lengths and prayers and garden-keeping and cooking and hosting and sewing apply. Anne herself rebels against plenty of these rules, but being only one individual, she does not dismantle them wholesale. In fact, Montgomery suggests that having the rules to rebel against—and sometimes follow—develops her personality for the better.

The Cuthberts decide to adopt Anne out of a sense of duty—one of the unsexy and uninteresting virtues that bind their society together. Abiding by those norms may sometimes squelch personality, but it also allows for a coherent community of mutual care. The same uptight, rules-based judginess that caused Avonlea to never forgive Anne over the blue hall secured her a place in Marilla and Matthew’s home—the sense of a duty to something bigger than oneself.

All of us deeply crave the comfortable awareness of belonging that fictional worlds, from Stars Hollow to the Shire, offer us a glimpse of. But I think we underestimate how, especially in the United States and other “first-world” countries, we have systematically dismantled the culture of concrete expectations that makes worlds like these possible. There have been many good reasons for this, historically. Societies with concrete expectations can metastasize into cults or oppressive regimes. I appreciate living in a place where, as a woman, I can get any job I want, wear whatever I want, say whatever I want. In fact, all of us can do or say almost anything we want in almost any context.

But that freedom comes with a price—the unwritten stories that used to make us feel like we belonged. I don’t think we want to go back to Avonlea. But I do think that, when we’re talking about building community, we may need to ask what rules we are willing to live with.

Love this. Anne is perfect spring-time reading. I do think the community--and the rigid rules that govern it--soften a little with exposure to Anne's free-spiritedness. Or at least she allows certain characters, over time, to understand that a rigid adherence to the rules is not the only marker of a good person.

Love your point about individualism and community. As a parent who is looking forward to the time (soon approaching) when I might be able to read Anne with my oldest, I've been thinking a lot about why this story has meant so much to me, and why I want to share it. And I think a big part of it that Anne's story is really about how a precocious child can grow into a full person, and why this really can only happen within the context of a community of care--which will constantly be pushing back against some of your flights of fancy while also still loving you precisely because of them.

There's just something incredibly powerful about that (very simple, but very profound) realization that Anne needed Matthew and Marilla exactly as much as they needed her. And, more broadly, that she needs Avonlea as much as Avonlea needs her.