As many have observed, we’re not in a secular age so much as we are in an age of newly revived superstitions—manifestation, the law of attraction, grimoires, tarot cards. Mugs that say “what’s up witches” and “basic witch.”

This was the case even before we had Grimes telling TIME that “killing God was a mistake” and Ezra Klein opining that, in recent history, “we’re re-entering a slightly more mystic, mythic turn of the wheel.” A photo of a woman praying for the recovery of Pope Francis went viral a few weeks ago, contributing to the sense that the Roman Catholic “aesthetic” (sometimes conflated with the aesthetics of Orthodoxy and astrology) is on the rise:

The fact that we label these religious/mythical frameworks as “aesthetics” shows how much our contemporary way of framing questions still dominates this conversation, but there is something to it. As Klein points out, the technology-first, “empirics and technocracy” approach to the world that raised atheists like Bertrand Russell and Christopher Hitchens to superstardom was itself a kind of aesthetic—or better, a narrative lens through which we chose to see the world from, say, the 90s to the 2020s. We had put the hippie movement on the shelf, spooked by its excesses. Now, as our empirical narratives fail, as planes are falling out of the sky and powerful mythologies fight it out on social media, we are realizing that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy (Hamlet 1.5).

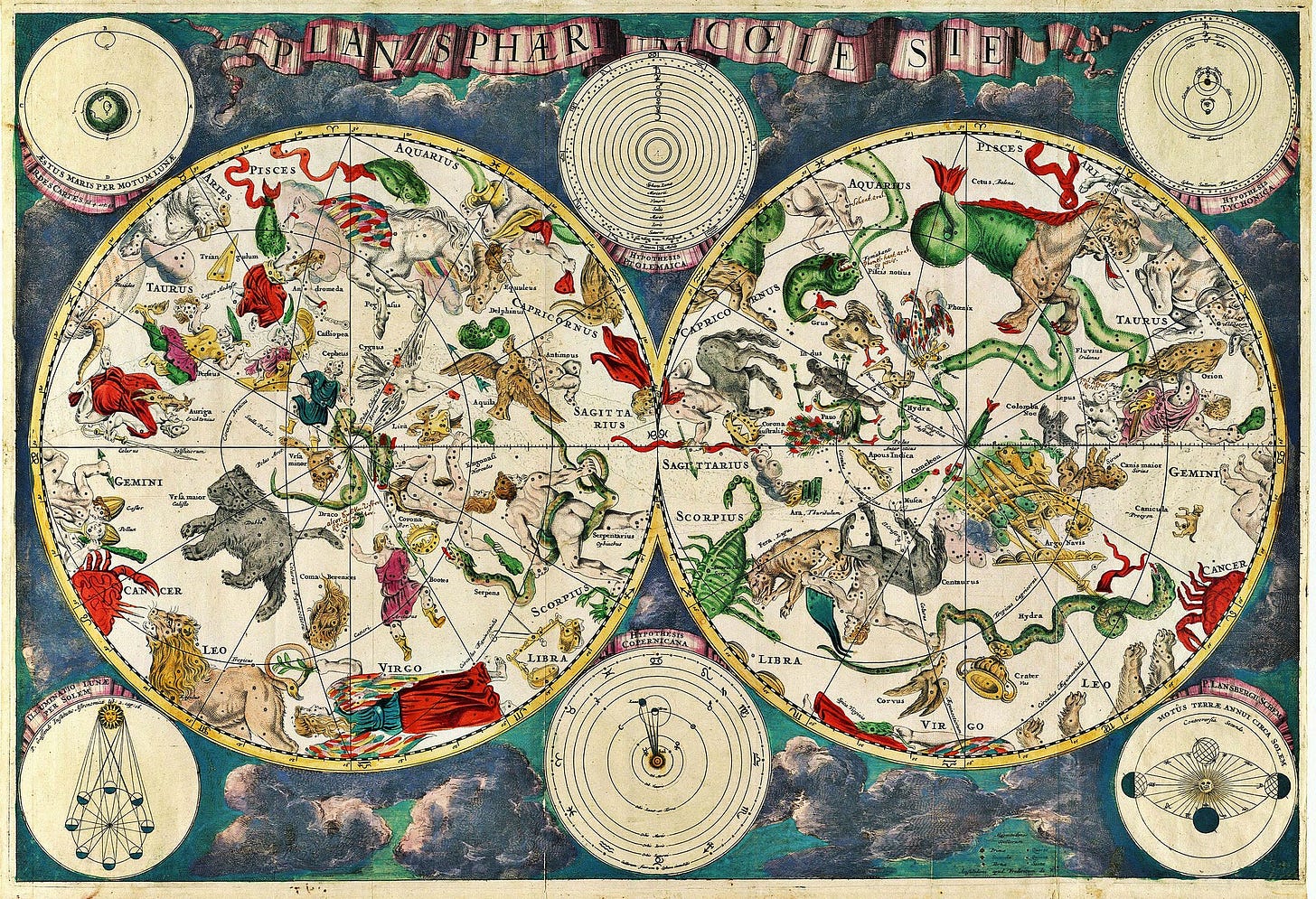

Setting aside the hotly-debated and probably unsolvable question of whether Shakespeare himself was a Roman Catholic recusant, I think people sometimes underestimate how much Shakespeare wrote from an Elizabethan Catholic cultural “aesthetic” that incorporated some awareness of the stars as a matter of course. We all know the “star-crossed lovers” Romeo and Juliet. As today, astrology often took the form of a half-joking personality test: In Much Ado About Nothing, Don Pedro says to the play’s witty, sparkling love interest Beatrice, “to be merry best becomes you, for out o’ question you were born in a merry hour.” Beatrice responds with one of her clever speeches: “No, sure, my lord, my mother cried, but then there was a star danced, and under that was I born.” Benedick, attempting to write a love poem to Beatrice, says in despair, “I was not born under a rhyming planet” (5.2).

Shakespeare’s plays are haunted by mythical goddesses and mysterious ghosts alongside flesh-and-blood friars and priests, more or less obscured liturgies, and the theological debates and concerns of his time. It is likely that Shakespeare traveled to Rome in his youth: the home of both classical mythology with its constellations and gods and the spurned Roman Catholic pontiff. In our own day, orthodox Christians (I think correctly) consider conflating the two to be a syncretistic move. But perhaps Shakespeare would have found himself at home in the present era, when the uninitiated lump together all the things that they do not understand—the papacy and the stars—into a vague sense of numinous mystery hovering over the banal everyday.

Often, grasping at that mystery takes the form of an attempt at control. Astrology gives you the option to explain everything about yourself, and everything that happens to you, in terms of the stars. You cry a lot because you are a Pisces. You are pushy because you are a Leo. You had a fight with your mom because Mercury is in retrograde. It’s the new moon, a great time to start things anew—not just a Wednesday in January when 28 bodies have been pulled from the freezing Potomac.

With this in mind, it’s tempting to argue that this mystical phase is not so different from our previous empirical phase as we might imagine. These charts and symbols provide a commodity that is in desperate demand—the illusion of control, the perception of intelligibility. The Red Scare girls authoritatively look up star charts for famous politicians, explaining their lying ways through unfortunate star alignments. There’s a spot for your star sign on most dating apps. Astrology tells the story of your own life to you in terms that you can understand.

But Shakespeare also shows us the limits of this organized vision, a world sorted by the stars: Cassius, in Julius Caesar, says “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings” (1.2). Despite Shakespeare’s deft use of classical mythology and astrology, in his presentation they fail to have explanatory power. In a moment of strange clarity before his death, the same Hamlet who told Horatio to be open to “more things in heaven and earth” seems to have gained an insight into what those things are: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, / Rough-hew them how we will” (5.2).

In The Tempest, in a speech often read as Shakespeare’s own farewell to his creative power, the sorcerer Prospero says, “I’ll break my staff, / Bury it certain fathoms in the earth, And deeper than did ever plummet sound / I’ll drown my book” (5.1). Having faced the limits of earthly magic, Prospero begs the audience to intercede for his soul in the epilogue:

Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free. (5)

At its root, an openness to “mystical aesthetics” is an openness to something more—something that we want much more desperately than we want control. As Tara Isabella Burton, author of Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, puts it in her essay “I Spent Years Looking for Magic—I Found God Instead”:

I had been—like everyone else—a teenage Wiccan, but how much magic I practiced, over the years, varied with my stance on nothingness. There were years that I read Tarot obsessively, and years where I didn’t ask the cards any questions at all. There were years that I set up altars in my dorm rooms and years where I never bothered, years where I felt nothing, years where the world seemed too bereft of significance to bother.

I did not like those years.

The occult years, on the other hand? These were the years that I raged and wailed and called down innumerable forces from the heavens.

If modern society on the whole is indeed developing a new openness to mysticism, I think it heralds more than merely the change of one aesthetic for another. At my most hopeful, I think it could be a sign of what some have called “re-enchantment.” In C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle, the characters who appear to be ultimately damned are not the many who mistakenly worshipped false gods but the few who chose to be enclosed upon themselves and refused to be “taken in”: “the Dwarfs are for the Dwarfs.”

As we are confronted more and more with things beyond our understanding, as we lean toward mysticism, I hope we will lose our fear of being taken in. Perhaps that means we will be taken in a few times, by Magical Self-Care Tarot and chart compatibility on Tinder. But Shakespeare suggests that, if we take a tiny step into the pool of things that we do not understand, we may eventually encounter something limitless.

Here's a question related to how mysticism is often a mode of aesthetic: Why moderns scoff so easily at the superstition of zodiac readings, as though it's ridiculous that those who are born in the same 30 day time frame would have similarities on the average, and yet when we increase that time frame to a span of 10 to 20 years, and call it names like "Baby Boomer", "Gen X", "Millennial", and "Zoomer", it's now perfectly rational to expect this cohort to have similarities across the average? Is generational obsession simply star signs for a materialist age?